THE LAB #26: From internal API to insights.

Excerpt

Getting insights on the automotive industry by scraping a car resell website.

When approaching a new scraping project, a good study phase is desirable if not necessary. One of the first steps is to understand how the website works: if it’s a website with dynamic content, like products on e-commerce, it means understanding how this data is gathered.

Very often, this is done via APIs: according to the page you’re loading, a request to an internal API endpoint is made and the results are shown on the front-end. Later in this post, we’ll see how to spot these APIs with your browser and use them to scrape data from a website.

If APIs are available and they return all the data your scraper needs, these should be used by the scraper. APIs are usually more stable than HTML code, they’re made to be queried (with proper throttling), and there’s no overhead in the responses, making the scraping more lightweight on both the server and the bandwidth aspects.

And when no API is available?

In case there are no APIs available, we should check the HTML code and look for some JSON containing the data we need. It’s not rare, especially if websites are developed in Next.JS, to find in the HTML some tags like

<script id="__NEXT_DATA__" type="application/json">

and then the JSON containing the data that populates the dynamic part of the web page.

This is the second-best approach for web scraping: using the JSON embedded in the HTML code, while there’s no advantage in bandwidth, at least it should be more stable than simple HTML scraping.

Last but not least, if there’s no API or JSON available, we are obliged to proceed with writing our selectors for the plain HTML code.

How to find internal APIs on a website

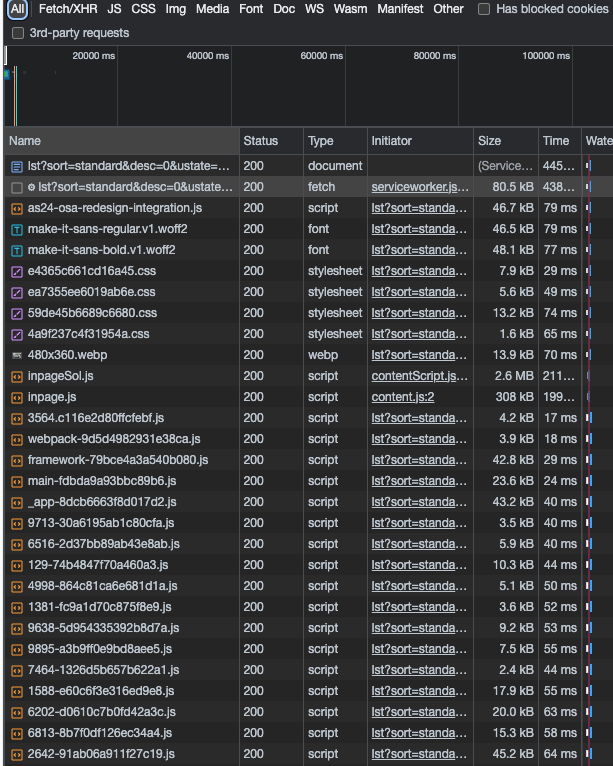

As we said before, when there’s some dynamic content on a website, there’s a chance that it’s loaded by an internal API and we can intercept it using the browser.

The way I usually observe what’s happening under the hood of a website is by opening the browser’s developer tools, on network tab.

[

With this view, you can see what’s happening in your browser, in real time. You can track the requests happening in background, typically by user tracking services, or when you click somewhere on the website, you can see what you trigger by doing so.

Let’s look for an internal API in a real-world website: autoscout24.it. It’s a website listing new and used cars, in Italy and Europe and, as mentioned before, this kind of websites with dynamic content are the ones that probably use APIs in the backend.

[

With the network tab open and cleared by previous calls (use the 🚫 icon to delete everything), let’s click on the yellow button and see what happens.

[

Many items are shown but nothing really useful at the moment. We have in first place the page itself with its HTML code, then a JS Worker called to fetch data in backgroud that doesn’t return anything and then a list of JS scripts and images to load. To get a clearer view without getting flooded by these scripts and images, we can filter by Fetch/XHR calls, where usually API calls are listed.

[

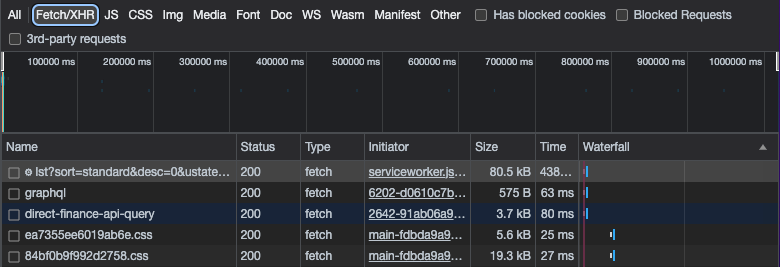

By clicking on each of them, we can see their response, headers and other details but none of them has in the response the data we’re seeing in the page. Let’s retry the same by clearing this view and clicking on page two.

[

This looks like the API we’re looking for! I’m not a front-end developer but I suppose that when we load the first page, the JS worker runs the query and injects the results directly on the HTML. Then, when we open the next page, data from the worker’s response should be passed again to the new page, and that’s why we see the API exposed, so I always recommend to load several pages on the target website to find and understand how the API works.

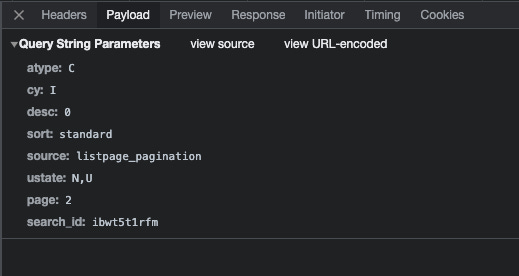

Since it is an internal API, we won’t find any publicly available documentation about it, so we should proceed with a bit of reverse engineering of the parameters.

Because it’s not relatable to other websites, I’ll keep it short here, but generally speaking we need to have a look at the payload tab and understand what are the parameters we should care of to correctly scrape the website. In case of GET requests, you’ll see the parameters passed in the URL, while when you have POST requests you’ll see the actual payload of the call.

[

Use Scrapy to query APIs

After understanding how the API work and which parameters are meaningful for our extraction, we can easily use the API endpoint as a target for our scraper.

As usual, you’ll find the full code on the GitHub repository for paying subscribers.

If you don’t have access to it and you’re a paying subscriber, please write me to pier@thewebscraping.club, I need to give you access manually.

Having the API available it’s a good starting point but the job is not over. Every website has its peculiarities and implementing the solution can hide unexpected challenges.

Limited pagination

Ok, you’ve implemented the code for your scraper for reading the API you’ve just found and guess what? Instead of having 300k+ cars on your output, you have only 400.

That’s what happened to me during the writing of this article and, while trying to figure out to discover what happens on page 21 that broke the scraper…. well I’ve found out that there’s no page 21.

Every query you make on the website, it returns at max 20 pages of 20 cars each, even on the website itself. You need to add some filters to it, like showing cars for only one vendor, one model and still it’s not enough. Probably you need to dig on a more granular set of filter but it’s out of the scope of this article, so we limit to query the website only by car model. We’ll not get everything but it will be enough to show something interesting.

Not everything is on the API

When implementing the recursive call of APIs, first for every vendor and then, per each vendor, selecting its models one by one, I’ve figured out that the results of the API call for the single vendor cars don’t have the codes of its model!

This means I need to make some back and forth between the vendor HTML page and its API call to get all the list of codes of its car model and then call again the API filtering by vendor and car model.

As we mentioned before, inside the HTML there’s the JSON with the data shown on the front-end and, for some reason, has more data than the API, so we’ll use that for getting the car model ids needed for filtering the requests.

Creating the data model

Since I didn’t have a specific business need and not being an expert in the automotive industry, I could postpone the creation of the data model of the output after having a look at the API results.

Ideally, this should have been done in the first steps, before start coding, but you’ll never know what you’ll find out in the API results. In fact, it could be that only a portion of the data contained in the APIs is shown on the website and you could discover some hidden gems there.

Enjoying the results

After implementing the whole scraper, we’ve got approx 160k cars on our output file, around 50% of the total number of cars available on the website but still good enough to play around with some data viz and good old SQL queries.

Car depreciation during time

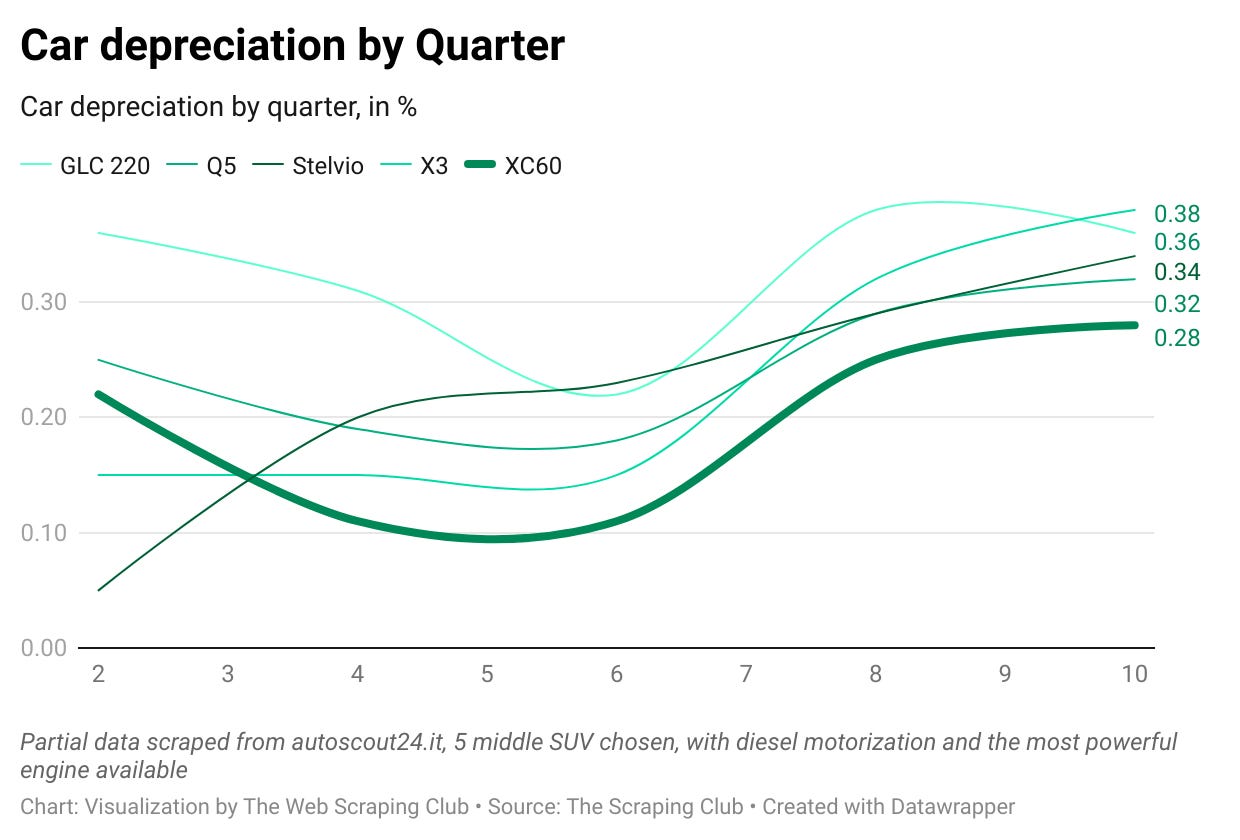

When choosing a car, its value over time is one of the main things to consider. From the data we scraped, we can take more informed decisions.

In this brief example I’ve chosen 5 medium SUVs, the Mercedes GLC200, Audi Q5, Alfa Romeo Stelvio, BMW X3 and Volvo XC60. To reduce the variables, I’ve chosen the most powerful diesel motorization available per each car and grouped the registration date in quarters.

Given so, without considering the amount of Kilometres they’ve run and their setup, I’ve calculated how much the average price per quarter is far from the average selling price of a new model.

Considering that the model is inaccurate and data is partial (so if you’re really interested in this analysis you should dig a bit deeper), we can see that these type of cars, after 30 months, are valued at the 60-65% of their initial price, with Volvo that seems to keep more its value over time.

Again, I would be careful in extracting conclusions, I’m only playing with the partial data I’ve got just to show the potentials of this kind of web scraping projects.

[

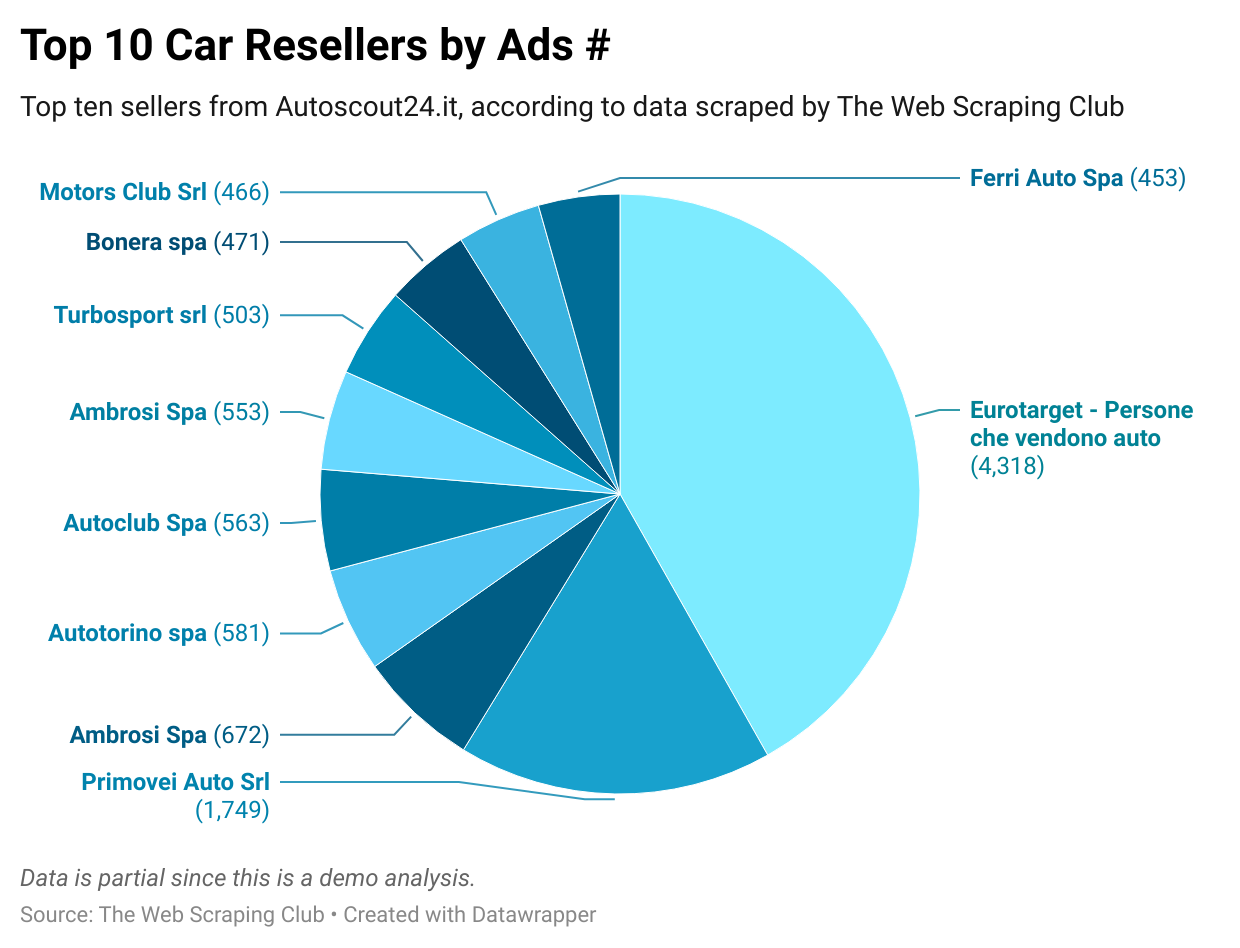

Share of selling cars, by seller

Let’s say instead you’re selling a service for car resellers, you’re entering in a new market like Italy and don’t know literally from who to start.

By scraping a website like Autoscout24.it gives you the idea on who are the key players in the market by simply counting the number of ads per seller.

[

Final remarks

In this article we’ve touched several aspects related to web scraping.

-

From a technical point of view, we’ve seen how to inspect an internal API using your browser.

-

Then we coded a scraper that uses it, bypassing also the peculiarities of this single website autoscout24.it. I didn’t want to make this article even longer by explaining the code, you can find it directly on the GitHub repository.

-

And last but not least we’ve seen some analysis we could extract from the data. They are based on partial data but give an idea of the high potential of the insight you can get after scraping properly and fully a website.